Fine Wine: The Liquid Investment That’s In 28% Of HNW Portfolios

When you think of fine wine, you probably imagine sipping a rare vintage in a swanky restaurant rather than a serious investment opportunity. Yet what’s particularly attractive to investors is the relative stability of fine wine prices during bouts of stock market turbulence.

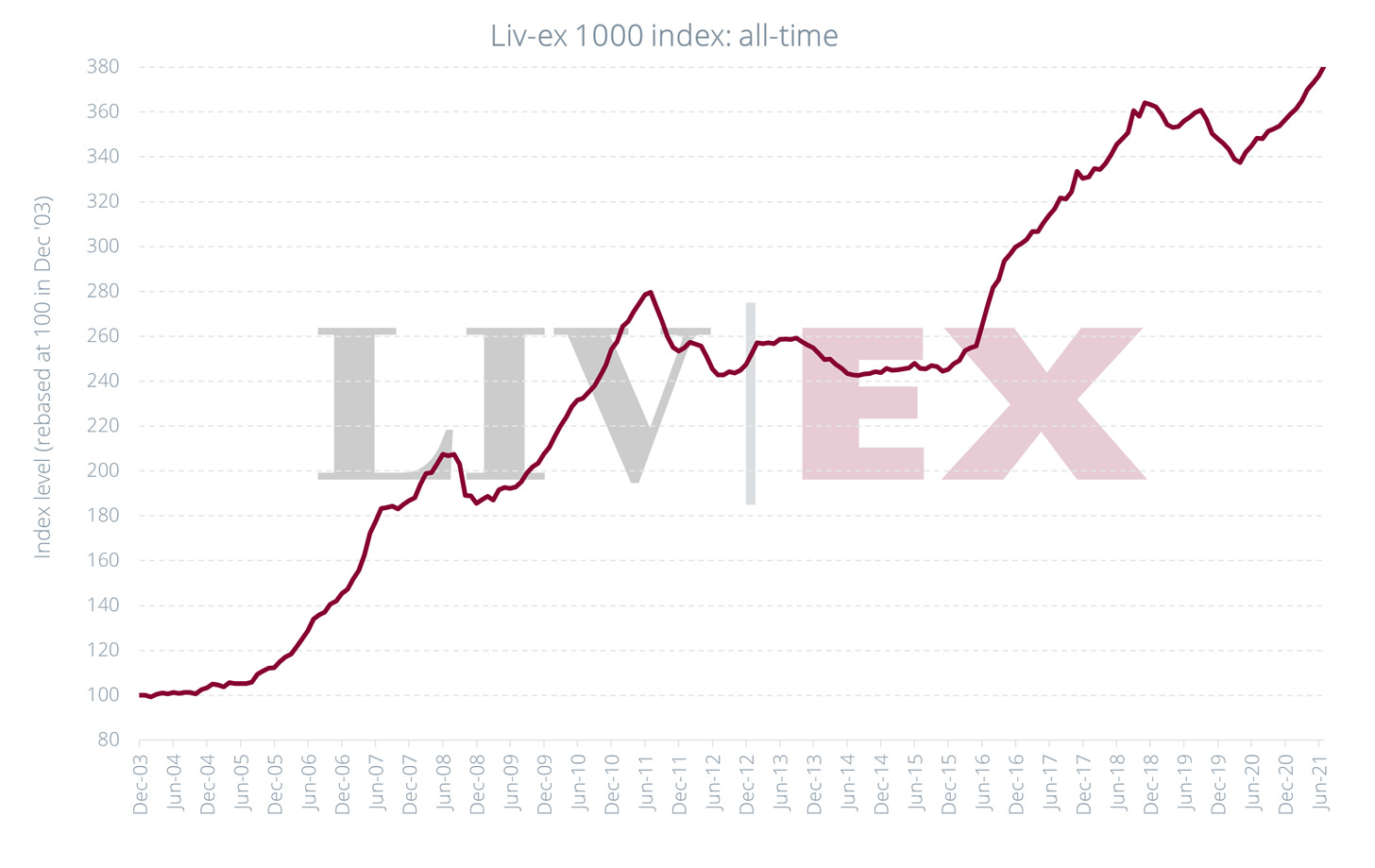

Most investors are all too well aware that in March 2020 the S&P 500 fell by 25%. In the same month the Liv-ex 1000, an index which tracks prices of 1000 iconic fine wines, dropped by just 4%. It’s no wonder that 28% of wealthy individuals have a fine wine collection and 23% plan to own one in five years time1. Let’s look at how fine wine measures up to other investment classes and what to consider before you add a case or two to your portfolio.

Market Overview

Investment-grade wine accounts for just 0.1% of the whole wine market, with the secondary market for fine wine currently worth around $5 billion. It’s largely dominated by France’s Bordeaux wine region which is home to the five legendary First Growths of Château Latour, Château Lafite Rothschild, Château Margaux, Château Haut Brion, and Château Mouton Rothschild.

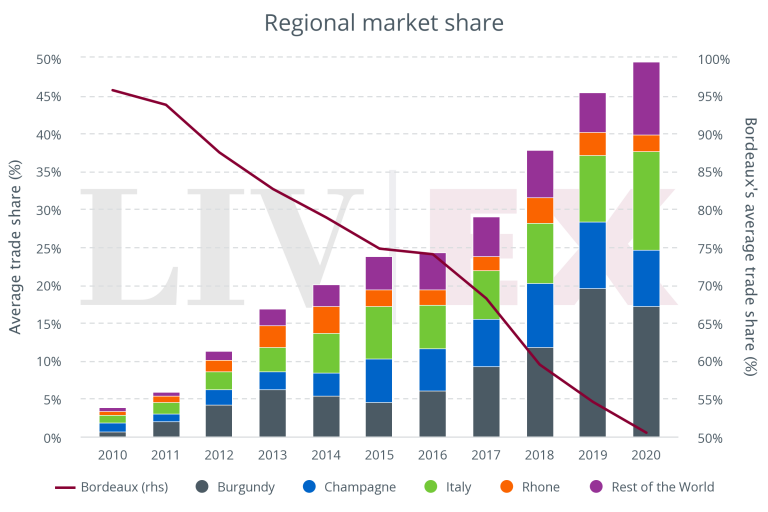

However, in recent years the market has broadened considerably with Bordeaux’s market share shrinking from 95% in 2010 to just 42% in 2020. Big gains have been made by Burgundy, Piedmont, Tuscany and Champagne in particular, as well as iconic wineries like Screaming Eagle in California and Penfolds in Australia.

Source: Liv-ex

Wine prices are driven by a complex web of factors including pedigree, vintage quality, rarity, and the wine’s ability to age. Unlike most other commodities, wine is unique in that it’s made to be consumed. Over time the availability of specific vintages of rare wines from legendary producers like Domaine de la Romanée Conti contracts. This in turn drives up prices for the remaining stock, bringing big gains for investors who are prepared to hold out for the long-term.

Key Players

The wine investment world can be loosely divided into two general categories. The first is more traditional wine merchants who specialise in sourcing top quality investment-grade wines direct from blue chip producers. A great example is Millesima in Bordeaux which sources top Burgundy and Bordeaux for private investors all over the world. The advantages of these types of firms are their top-notch knowledge and access to rare wines with impeccable provenance, but they may be limited when it comes to giving strategic financial advice on your investment.

The second category is dedicated wine investment firms which are often run by former bankers and financiers. Great examples are Cult Wines which offers fully-managed wine investment services and the UK-based Amphora Portfolio Management which has even created its own algorithm named MARRVIN (Mathematically Automated Risk and Relative-Value Investment Number-Cruncher). These typically offer great investment advice and portfolio management, but they can be limited when it comes to sourcing and identifying high potential wines.

There’s also a third emerging category of tech-driven wine investment firms spearheaded by Vinovest which enables investors to build a portfolio on their dedicated app.

How Does Wine Compare To Other Investment Classes?

Investors commonly use SWAG (silver, wine art and gold) for asset-backed portfolio diversification and a hedge against wider market volatility and inflation. Fine wine tends to hold its value well even during economic crises, providing strong downside protection thanks to its relatively low stock market correlation and status as a luxury asset. In 2008 during the Great Recession the S&P 500 plunged 38.5%, while the Liv-ex 1000 fell by just 0.6%.

Source: Liv-ex

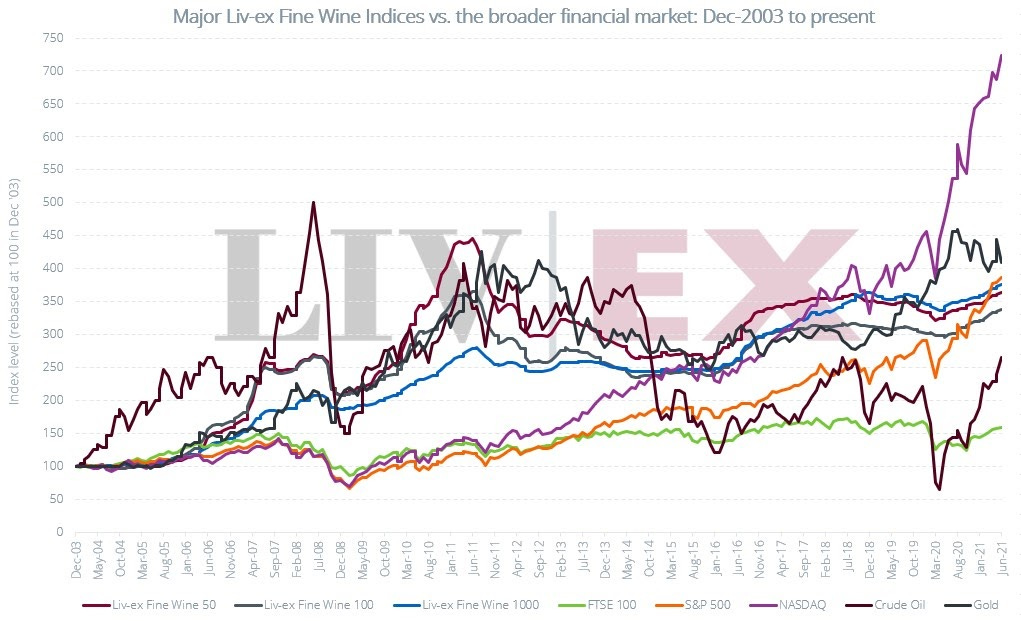

Few wine collectors can expect to get rich from their liquid assets alone, but most big players in the market like Cult Wines promise an annualised return of 5-9% on fine wine. This compares pretty favorably to the stock market over a long-term hold. Research by the Liv-ex fine wine trading platform in June 2021 showed that their Fine Wine 50 and Fine Wine 1000 indices are up 263% and 276% respectively since 2003, compared with 286.5% for the S&P 500.

Source: Liv-ex

Fine wine can also have very interesting tax implications and arbitrage opportunities depending on your tax residency and income thresholds. Capital Gains Tax does not usually apply to any profits made on fine wine in the UK and Hong Kong. In the US the picture is more complex and should be referred to your accountant or tax advisor.

Risks & Additional Costs

If you’ve seen the 2016 film “Sour Grapes”, you’ll know investors need to do their homework carefully to avoid unscrupulous brokers and outright wine fraud. Infamous wine fraudster Rudy Kurniawan conned investors out of millions of dollars by blending up copies of rare wines in reused old bottles. It’s best to only buy from reputable merchants and brokers who source their wines directly from the winery. Anything sold at an online auction by a little-known seller should immediately raise red flags!

Another potential risk is that changing future tastes will diminish demand and may impact your profit. Liquidity can also be challenging with luxury assets. Most wine investment firms prefer to sell client wines to other private clients, the hospitality trade, or at auction. Options are much more limited for private investors who may have to sell through a broker or merchant on a commission basis.

Other issues that you don’t get with good old stocks and shares include storage costs and good insurance to cover the current replacement cost of your bottles.

Identifying Investment-Grade Wines

Wine investment firms typically look for wines from big name wineries that are produced in strictly limited quantities and enjoy high demand amongst collectors. Vintage is particularly important since weather conditions in most traditional wine regions like Burgundy and Bordeaux can vary dramatically from year to year. As bottles of Bordeaux 2005 began to be opened in 2015, critics and collectors realised this was truly a vintage of the century. The price of Chateau Mouton Rothschild 2005 alone rose 20.7% in the first month of 2015. In other vintages investors may lose money if the quality is later downgraded.

Potential investors should also be aware that ratings from top wine critics and publications like Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate can make or break a wine. For example, Robert Parker’s re-evaluation of Chateau Haut Bailly 2009 to a perfect 100-point score in 2014 kicked prices up by 45.2% in just three days from $1066 per case to $1790. Good reviews and great vintages can create frenzied demand amongst collectors, driving up prices in a matter of days or weeks. It goes without saying that the opposite is also true.

Maximising Returns

Once you know what you’re looking for, the final piece in the puzzle is to understand how to maximise your returns. It’s wise to build a diversified portfolio which includes bottles from a variety of producers, vintages, and global wine regions to minimise your exposure and risk. Most portfolios will include blue chip wines from top producers as well as lesser-known wineries with strong potential. Investors should also expect to tie up capital for the long-term with most investment-grade wines showing decent returns 5-10 years after release.

En Primeur or “Wine Futures” campaigns are a smart way to enter the market ahead of other investors and secure promising young wines at favorable prices. The most famous is the Bordeaux En Primeur campaign every spring where top chateauxs offer wines from the previous vintage that are still in the barrel. It can be very difficult to access these wines since allocations are strictly controlled. Those fortunate or well-connected enough to acquire top-scoring wines from good vintages can often expect a big uptick in value when they are bottled and officially released around 18 months later.

Another strategy for uncovering alpha opportunities is to look for emerging wineries which have the potential to become “unicorns”. These might be visionary young wineries in old school wine regions or established wineries in underdeveloped regions that are becoming more collectable.

A great example is Liber Pater in Bordeaux which was founded by maverick young winemaker Loic Pasquet in 2006. Pasquet released just 240 bottles of his 2015 vintage at $33,420 per bottle, making it one of the most expensive wines ever sold. The media attention generated by this spectacular release helped push up prices for previous vintages, favoring investors who were early to the party.

Just like identifying growth stocks, picking out these up-and-coming wineries needs an expert eye. Good terroir, a term used by the industry to describe the soil and climatic conditions of a wine region, excellent vineyard management, talented winemaking, and strictly limited output are the key when looking at production. Artisanal production methods are common, with most fine wine producers picking their grapes by hand and applying organic and biodynamic practices in the vineyard and winery.

Gauging the potential success of a particular wine on the secondary market is more challenging. Most young wineries that make it big benefit from outstanding scores from top wine critics, visionary and pioneering winemakers who aren’t afraid to try new things and well-resourced marketing departments.

Drinking Your Investment

Reading this may have whetted your appetite for fine wine investment, or at least a decent glass of Bordeaux. And that brings me to one final point which might just swing it for you - the unique twist with fine wine holdings is you can always drink your investment. Now that’s something you just can’t do with stocks, bonds, or even a gold bar.

Notes

Source: Ledbury Research and Barclays bank, “Wealth Insights: Exploring the Motivations Behind Treasure Trends”